Hemp fiber was common in colonial America, it was used for a thousand everyday purposes from ropes to tablecloths to paper. Hemp grows great in America and was in constant demand. But hemp was not a profitable crop because of the high labor costs to prepare the fibers. The one exception was in 1800s Kentucky, where slave labor processed hemp until the Civil War.

Without hemp, slavery may not have existed in Kentucky at all since none of their other crops required the use of bondsmen.

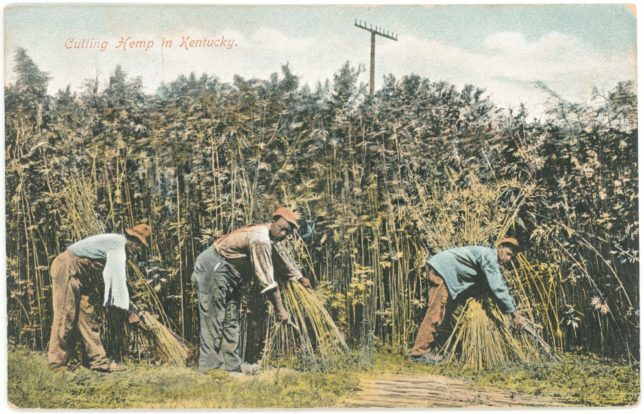

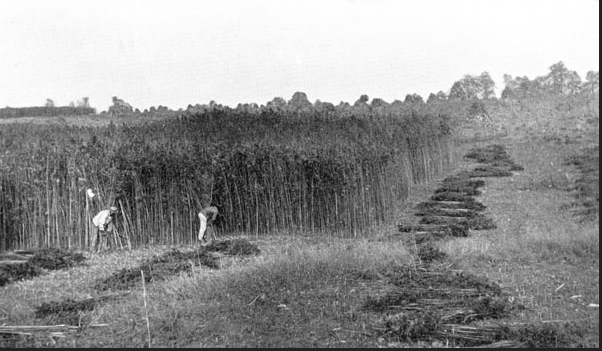

Hemp is Back Breaking Work

Harvesting, beating, and hackling hemp was difficult and dirty work. It takes strength to work the fiber all day, and years of experience to get the skills to do the work well.

James Hopkins wrote in his book, “A History of the Hemp Industry in Kentucky”:

“Kentuckians sometimes referred to hemp as a “nigger crop,” owing to a belief that no one understood its eccentricities as well or was as expert in handling it as the Negro. A Lexingtonian stated in 1836 that it was almost impossible to hire workmen to break a crop of hemp because the work was “very dirty, and so laborious that scarcely any white man will work at it,” and he continued by saying that the task was done entirely by slave labor.”1

But it was a Desired Job

Despite the difficult labor, working in the hemp fields was a desired job among slaves because it was task work rather than gang work. Gang work took place in the cotton fields where a whip-carrying taskmaster drove the slaves to work hard. In task work, the slaves were given a quota for the day and left unsupervised to do the work themselves. If a slave exceeded his quota he could earn wages for additional production or have free time. 2

Slaves earned money in the task system. For breaking hemp, they were typically paid a penny for every pound over the 100-pound quota. A good worker could break 300 pounds a day, earning about $2. Work in the hemp factories was task work as well. Some slaves earned enough money to purchase their freedom.

Slaves Sang While They Worked and Earned Wages

A northern visitor to a Lexington, KY ropewalk in 1830 described the slaves as “stout, hearty, healthy, and merry fellows,” who sang while they worked. He continued, “each one is paid for what he does..this keeps them contented and makes them ambitious…I have never seen a happier set of workmen than these boys; there was no overseer.” 3

There were similar reports of well-treated slaves in Kentucky that were not appreciated by northern abolitionists. They preferred to hear tales of beatings to give support to their cause. No one would choose to be a slave, but the slaves were truly better off in the hemp fields than in the cotton fields. There are records of slaves earning $900 in the task system, more than some white workers were able to earn and save in their lifetimes.4

A Few Slaves Earned Their Freedom

William Hayden was a slave who earned his freedom doing hemp work and later wrote a book about his life. He went to work in a KY ropewalk when he was young and was so proficient that he was taken into the master’s house where he learned to read and write. Hayden was considered to be the best spinner in the country and eventually became a factory foreman, respected by the white men. At age 39 he purchased his freedom and moved to Cincinnatti where he owned his own barbershop.5

Slaves in the hemp industry were happier than other slaves beacuse they were given freedom and wages. But one can imagine that the medicinal qualities of cannabis contributed to their good spirits as well. Not everyone was capable of working hemp, only the strongest and most intelligent workers could do the job well, so it was a proud club.

Bad for the Slaves and Twice as Bad for the Whites

After hemp is harvested it must be “retted”, left in the fields or in ponds for weeks so that bacterial breakdown could enable the fibers to be separated from the stalks. Water-retting of hemp was rarely done in America, even though it produces a much higher quality fiber.

When hemp is soaked in a pond the water is poisoned from the resins, killing all fish and rendering it unsuitable for livestock. In addition, water-retting gives off a noxious odor that stinks of rotten eggs. It was believed that the odors were detrimental to all life in the vicinity. It was thought that the odors endangered the lives of the slaves, and were doubly perilous for white people.6

The Grand Staple of Kentucky

The first Kentucky hemp crop was grown in 1775, and by 1810 it was the state’s most important crop. At the peak in 1850, there were 8327 US hemp plantations that produced 40,000 tons, half in Kentucky, the rest in Tennessee, Missouri, and Mississippi. At the time, hemp was the third-largest farm commodity behind only cotton and tobacco in total production.

Congress levied tariffs on imported hemp in 1792, and by 1828 they had been raised to $60 per ton, encouraging a robust industry. Despite the tariffs, the USA consistently imported more hemp fiber than it produced, and that has remained true to this day. Russia produced most of the high-quality hemp used for shipbuilding.

The towering statesmen from Kentucky, Henry Clay, was a champion of hemp farmers throughout his career. Clay grew hemp on his estate and had up to 60 slaves of his own, despite his outspoken opinion that slavery was evil. Clay’s opponents called him a hypocrite and his fence-straddling cost him in his ambitions to become President.

Henry Clay, like Thomas Jefferson before him, embodied the paradox of the high-minded slaveowner. They recognized the intrinsic evil of slavery, yet were unable to separate their businesses from the practice.

The Kentucky hemp industry collapsed with the Civil War. Not only were the slaves freed, but the cotton industry was decimated, eliminating the primary market. Hemp was used in baling and bagging cotton. After the Civil War, the industrial revolution brought new iron wire cables and bands, while cheaper jute began being imported from India. Many farmers gave up on hemp and turned to other crops.

- Hopkins, Jame F. A History of the Hemp Industry in Kentucky, Lexington: University of Kentucky, 1951.

- Abel, Ernest L., Marihuana The First Twelve Thousand Years. Plenum Press, New York, 1980.

- Abel, Ernest L., Marihuana The First Twelve Thousand Years. Plenum Press, New York, 1980.

- Abel, Ernest L., Marihuana The First Twelve Thousand Years. Plenum Press, New York, 1980.

- Abel, Ernest L., Marihuana The First Twelve Thousand Years. Plenum Press, New York, 1980.

- Hopkins, Jame F. A History of the Hemp Industry in Kentucky, Lexington: University of Kentucky, 1951.