The northeast USA offers an interesting story of natural gas pricing as pipeline constraints limit the flow of gas from the bountiful production regions in the Marcellus and Utica shales to the enormous demand centers in Boston and New York City. Key chokepoints for the gas distribution are around New York City/Long Island and in New England. With production booming, gas prices have been held down at key pipeline hubs in Pennsylvania, while in neighboring states, Massachusetts and New York, prices are climbing.

As US shale gas production continues to grow, Henry Hub spot prices for natural gas have held steady through the autumn of 2014 at a little above $4/MMBtu. But falling temperatures across most of the country in mid-November caused natural gas prices to rise.

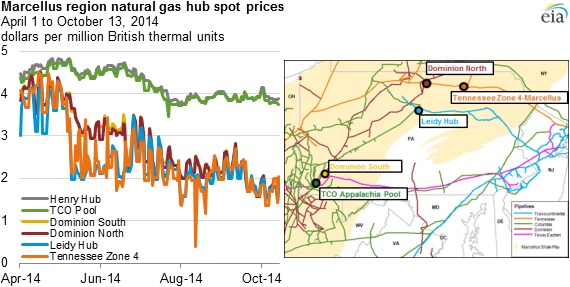

Since the summer of 2012, rising production of natural gas in the Marcellus has outpaced the growth of pipeline capacity in the region causing gas prices to decline and separate from the benchmark Henry Hub price. Price hubs in the central and northeastern portions of the Marcellus, where pipeline capacity is particularly limited have seen the sharpest drops.

Prices in Connecticut and Massachusetts spiked as high as $10/MMBtu in mid-November, while price at the Transcontinental Pipeline’s Leidy Line in the Marcellus was held below $3/MMBtu. The large amounts of backed up supply has also made regional prices volatile, dropping as much as $1/MMBtu on moderate temperature days when demand is low.

Natural gas transportation into New York and New England is highly constrained during times of peak demand. Winter temperatures create increased demand for heating in both residential and commercial sectors as well as demand for gas-fired power generation which represent nearly 50% of New England’s electric generation capacity. Past winter seasons have seen price spikes for natural gas and the pattern is expected to continue this winter season.

For decades, ever since the gas pipeline infrastructure was first laid down, the Northeast has been a major natural gas demand center. Gas was imported into the region from all available areas: the Gulf Coast; Midcontinent, Rockies, Canada, and LNG through the Boston terminal. In the past three years though, gas production from the Marcellus and Utica shale in Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio has grown substantially and shows signs of long term productivity. Gas production has gone from less than 3 Bcf/d in 2009, where it was for decades, to 18 Bcf/d in 2014 with projections of 30 Bcf/d by 2019.

Break-even prices for producers in the Marcellus and Utica shale regions suggest that the regions have strong foundations for growth. The break-even price for dry gas producers in the Northeast Marcellus are around $2.50/MMBtu and the price for wet gas producers in Southwest Marcellus are lower at $2.00/MMBtu. Wet gas producers are able to sell the condensates and natural gas liquids for a premium which takes pressure off the price needed for the dry gas.

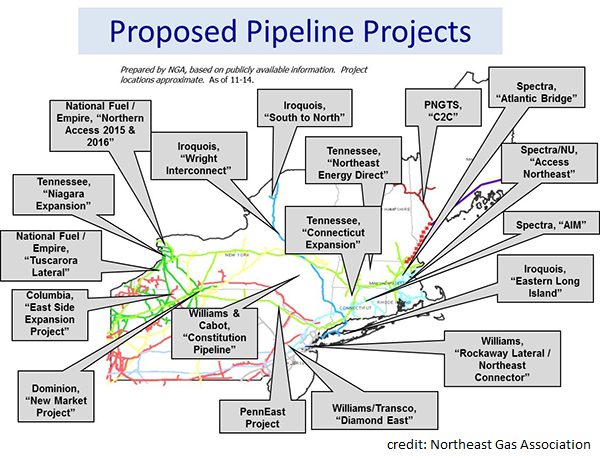

There are a number of pipeline expansion projects nearing completion or in the works that will help increase the capacity of gas to flow into the Northeast by up to 35 Bcf/d. New York and New England are not the only regions seeking Marcellus shale gas. Because of structural changes that new gas resources have brought, older pipelines into the Northeast are often going underutilized. The natural gas pipeline industry is working to modify the pipeline infrastructure to enable bi-directional flow and move up to 8.3 billion cubic feet per day out of the Northeast and into the Midwest and down to the Gulf Coast.

The enormous gas production from the Northeast is not just impacting the local markets. Gas producers have their eyes on markets in every direction, pushing out into the Midwest and Ontario and looking to the Southeast. The big prize market for gas producers is the Gulf Coast where there is expected to be dozens of gas hungry petrochemical facilities and LNG export terminals.

There are nearly 60 gas pipeline projects in various stages of development throughout the Marcellus and Utica shales. 41 of the projects will add capacity to move gas out of the region. There are five major corridors through which the pipelines flow: east to New York and New England, south via the Atlantic coast, southwest towards the Gulf, Midwest via Ohio, and North to Canada. These projects represent one of the biggest energy infrastructure changes in the USA in decades.

According to the EIA:

- Columbia Gulf Transmission completed two bidirectional projects in 2013 and 2014 that enable the system to transport natural gas from Pennsylvania to Louisiana.

- ANR Pipeline, Tennessee Gas Pipeline, Texas Eastern Transmission, and Transcontinental Gas Pipeline are planning to send natural gas from the Northeast to the Gulf Coast because of the potential of industrial demand and LNG exports from the Gulf Coast. These projects total 5.5 Bcf/d of flow capacity.

- The Rockies Express Pipeline’s partial bidirectional project (2.5 Bcf/d of capacity) is primarily to flow Marcellus natural gas to more attractive markets in Chicago, Detroit, and the Gulf Coast.

- The Iroquois Gas Pipeline’s bidirectional project (0.3 Bcf/d of capacity) will deliver natural gas from the Marcellus to Canada. Iroquois will receive gas from the Dominion, Constitution (expected in service in 2016), and Algonquin pipelines.

The reasons for modifying existing pipelines rather than constructing new pipelines include: lower capital costs, fewer permits, and less environmental impacts. At the same time, modifying pipelines to be bi-directional offers much greater flexibility to respond to changing market conditions in the years to come and maximize pipeline utilization rates.

Each pipeline project requires contracted customer commitments to proceed, pipelines are not built speculatively. Developers must also meet all federal and state regulatory requirements, permitting can be a time consuming and expensive process.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) is the lead permitting agency for interstate pipeline projects. FERC is an independent agency that regulates the interstate transmission of natural gas, electricity and oil. A FERC review of an interstate pipeline project takes from 5-18 months, with an average time of 15 months.

Published at FC Gas Intelligence, Dec. 3, 2014