Breaking Energy, Sept. 11, 2014 (.pdf)

The Energy Collective, Sept. 16

The Brookings Institute in Washington DC has come out in favor of lifting the U.S. ban on crude oil exports. Brookings hosted an event on Sept. 9 to unveil their new report titled “Changing Markets: Economic Opportunities from Lifting the U.S. Ban on Crude Oil Exports” written by Charles Ebinger and Heather Greenley and based on research provided by NERA Economic Consulting.

Charles Ebinger and Larry Summers. credit: Brookings Institute

Larry Summers, former economic advisor to President Obama, gave a speech at the event presenting the case why the ban should be lifted. The ban is a legacy policy from the 1970’s that is no longer relevant in today’s market. Price controls for oil were implemented in response to the OPEC oil embargo and the crude oil export ban was part of that policy. Though price controls were lifted in 1980 the export ban remained in place and was largely unnoticed because the U.S. was a heavy importer of oil and industry had no need for exports.

The situation has changed recently with the new production of tight oil from shale using hydrofracking. The tight oil is a much lighter variety than the American refiners are set up for and now a glut of Light Tight Oil (LTO) is emerging that is depressing prices and limiting production. Oil producers are forced to sell their oil at low prices or else invest in expensive new refineries which can take years to permit and construct. Another option has been to subject the crude to minimum refining, just enough to allow the oil to qualify for export, but these refineries have minimal environmental controls and the overall process is inefficient. The producers would prefer to sell the light oil overseas where appropriate refineries already exist.

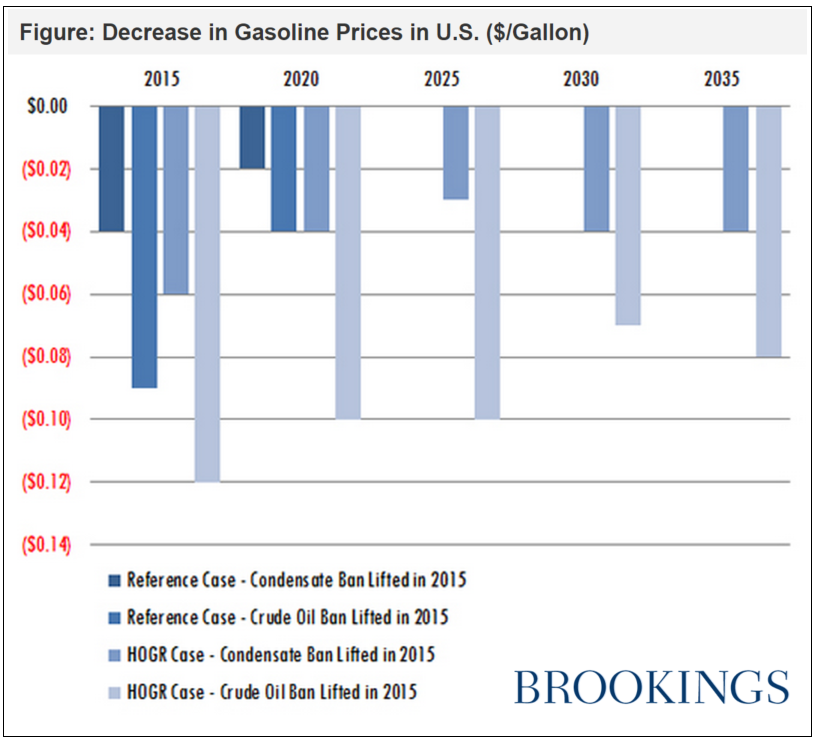

Brookings concluded in the report that lifting the export ban would help lower U.S. gasoline prices, despite claims to the contrary by many. Though analyst estimates vary, Brookings claims that gasoline prices would drop by around $.09/gallon if the ban were lifted soon. Additionally lifting the ban would boost U.S. economic growth, wages, employment and trade. Their analysis shows GDP could increase between $600 billion and $1.8 trillion by 2039, depending on how soon and completely the ban is lifted.

Lifting the ban will increase profits for producers (though reduce profits for refiners) and encourage more production. This increased production could U.S. oil output from 1.3 to 2.9 million barrels per day than under the ban. The increase in U.S. oil production helps lower world oil prices and U.S. gasoline and diesel prices, at least temporarily. U.S. oil refiners are also not forced into investing to modify their facilities to accept light tight oil.

There are global geostrategic interests at stake as well. According to Brookings U.S crude oil supplies will compete with Russian supplies and assist European and Asian allies in diversifying away from Russian supplies and away from contested seaborne routes in the South China Sea.

One major concern is the reaction of OPEC if the U.S. were to begin exporting crude. OPEC is not a monolithic entity and rivalries exist within the group. Saudi Arabia is by far the largest producer with the greatest capacity to modulate production in response to market conditions. Saudi leadership so far has downplayed concerns over U.S. production. Of greater concern to OPEC is a downturn in global demand or increased production from areas of strife such as Iraq, Iran, Libya, Angola and Nigeria all of whom have seen decreased production in recent years. These countries have far greater potential than the U.S. to disrupt markets with additional supplies. By OPEC standards U.S. export production would be small but could impact African nations that traditionally supply light sweet oil.

Environmental concerns that exporting crude will lead to more fracking which may threaten ground water, increased CO2 emissions, or increased transport of oil with potential accidents are appreciated by Brookings, but outside the scope of their report. The view on these environmental concerns was that they need to be addressed on their own merits. It is premature to know whether increased U.S. production would create more greenhouse gas emissions without evaluating whether U.S. production curtailed production elsewhere. And regarding the safety of drilling and transport those practices need to be regulated but are only tangential to the question of crude exports.

Larry Summers, who was not an author but echoed the findings in his speech, said that climate change is profoundly important but would not be influenced by oil exports, as opposed to the bigger question of moving society off of fossil fuels in general. Summers argued that the U.S. has been a strong advocate of free trade policies throughout the world and has long fought commodity trade restrictions so it is anathema to U.S. governing philosophy to continue the export ban.